|

So, back to last week’s ABG conundrum.

We were deliberately light with the information we gave you. If you’re serious about sitting the fellowship, you need to be able to work through an ABG. Calculating through this one you should have confirmed an isolated raised anion gap metabolic acidosis with appropriate respiratory compensation. That’s great, as far as it goes…..(We’re not going to get into the CAT MUDPILES debate here – Luke has made his thoughts on this perfectly clear in his ABG book…..) Even remembering there’s only 4 causes of a RAGMA, the numbers still aren’t very helpful in terms of giving a diagnosis. So, what other information can we glean? Fortunately this is an exam, not the real world. Let’s go to the information most people overlook – the questions. We asked: 1.What are the possible diagnoses? 2.Are there any further bloods you need to check? 3.Are there any other bedside tests you’d run? 4.Is there a rare antidote you might have to give this patient? In particular, if the answers to any of questions 2,3 and 4 were ‘no’, then what were we asking them for?? The only possible conclusions are: 1.There are specific further tests we should run both on bloods and the bedside. 2.There is an unusual antidote to be given. Then step back to the stem, and find the word ‘epileptic’. There’s no reason to put it in, unless it’s a pointer to the answer. So, to revise for this week, you need to find: -An anti-epileptic medication -That causes a RAGMA without renal failure or ketosis. -Whose pathophysiology can be measured with further blood tests. -That requires an unusual antidote. Good luck. If you know the answer feel free to take a punt on our facebook page.

0 Comments

This is the first of 3 weeks of posts. We’d love readers to play along and post up some answer suggestions on our facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/fellowshipexam).

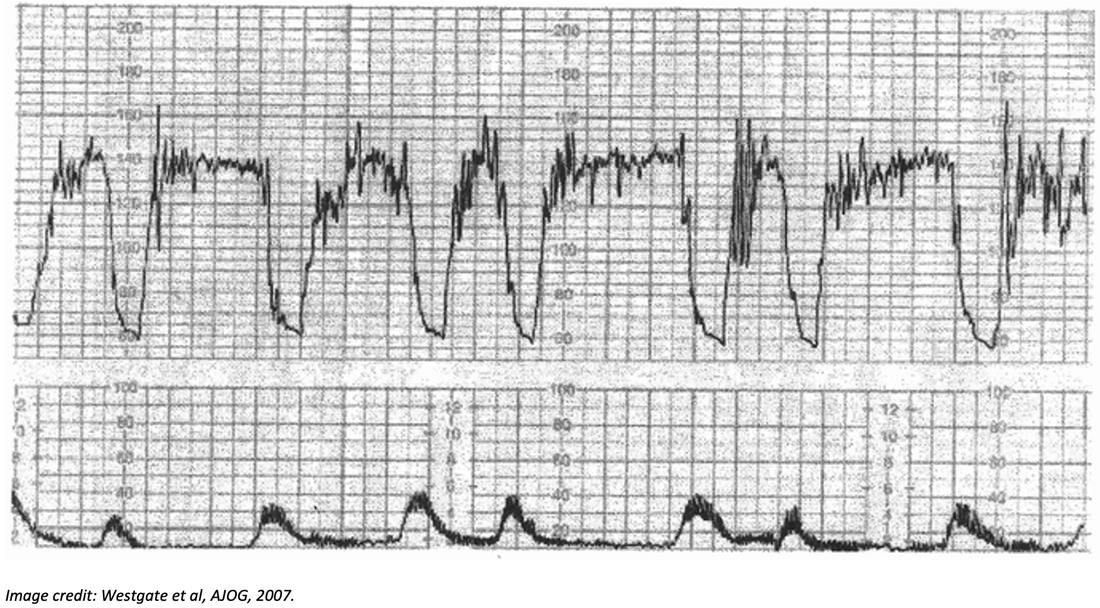

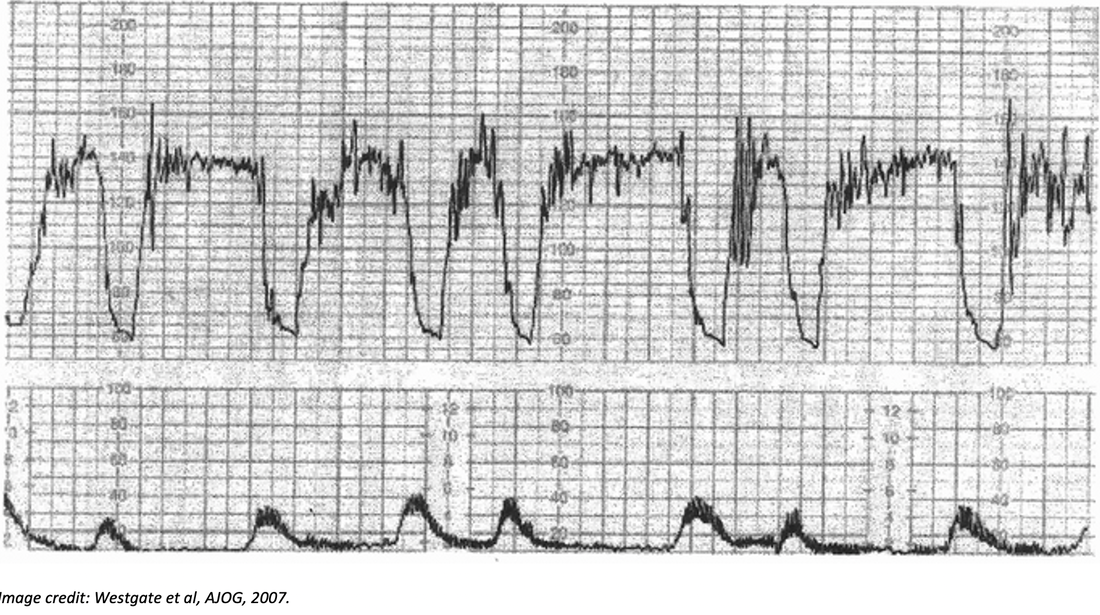

A patient presents semiconscious after an unknown overdose. His medical history indicates a history of epilepsy, but there is no medical record of his medications listed. Initial bloods in resus are taken: Venous gas: pH 7.12 pCO2 26 mmHg HCO3- 12 mmol/L Na+ 140 mmol/L Cl- 104 mmol/L Creatinine 60 umol/L Urea 4 mmol/L BSL 5.5 mmol/L Ketones Not detected. Lactate 10 mmol/L We’ve thrown this out in this week’s 5 point fellowship Friday to emphasise a couple of really important points about understanding the exam. Work through the ABG and calculate the acid base disturbances. Then ask yourself: 1.What are the possible diagnoses? 2.Are there any further bloods you need to check? 3.Are there any other bedside tests you’d run? 4.Is there a rare antidote you might have to give this patient? *Every piece of information you have been given is fair game for your analysis.* Share your thoughts on our facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/fellowshipexam. If you want to read an ABG/VBG in 5 steps go to the RESUS Page CTGs in the exam part 2: Everything you wanted to know about CTGs but were too afraid to ask.12/2/2021 The above CTG shows late decelerations, suggestive of foetal hypoxia (in this case a cord prolapse), and indicates a need for immediate delivery of the baby.

Below is a crash course on cardiotocography (yes, that’s what it stands for). If you want a more in-depth (but still user friendly) review, check out Geeky Medics.com. Here’s the big headlines. 1.The CTG measures 2 things: a.Foetal heart rate (above) b.Uterine tone (below). c.Each big square usually represents one minute. 2.The foetal heart rate will exhibit some variability around the normal FHR of 110-160/min. Normal variability is between 5 and 25 beats per minute. 3.A foetal heart rate of <100 is defined as bradycardia and is cause for concern. 4.Accelerations of heart rate in line with uterine contractions occur in a healthy foetus. 5.Early decelerations of heart rate (basically during uterine contraction) are also more likely than not to be physiologic. a.Note that there is some subtlety to this, meaning it’s probably not an ACEM fellowship exam topic. 6.Late decelerations begin (as above) with the apex of uterine contraction. They occur, because at maximum uterine pressure perfusion insufficiency is maximal. In other words, late decelerations indicate foetal hypoxia, and are an obstetric emergency. 7.If you ever see a sinusoidal CTG (as in a proper sine wave) it is a critical emergency and indicates severe foetal hypoxia, anaemia or foeto-maternal haemorrhage. That’s an absolutely “brass tracks” interpretation of a CTG. There is FAR more too it than that in real like (which is why it’s done by obstetricians rather than emergency physicians…) However, if what is above is what you take into the exam about CTGs, it’s probably enough to pass the question. We are big believers in investing time in high yield topics, rather than very unlikely ones. CTG is an unlikely one, and if you read and remember this, you probably need to read no further. We plan to make a bit of a FPFF series on “stuff you’ll never see, but just in case…”. If there’s other topics our readership wants us to take on, let us know by our facebook page. Stuff you’ll never see….but just in case. Occasionally the examination throws up stuff we just don’t expect will be present. Part of preparation is both casting a wide net so that it’s unlikely you’ve missed anything important, and also understanding that there is logic and rules to how the examination is played. Take the following question: You are called to attend a 38yo P1G0 woman who is 38/40. She has presented to your department with severe rhythmic cramping in the abdomen. A midwife has attended from birth suite and hands you a CTG which is shown below. Describe and interpret the CTG and outline your actions. So, before you think “this is completely ridiculous and would never happen in real or exam life”, there was a CTG question on a recent exam.

Step back for a moment, and ask yourself what you’d do with this. Next week, we’ll get a brief outline of CTGs into the FPFF. But, if you’ve never seen this before, take a moment and have a think about how you might answer. Can you use exam smarts….? Here’s an example of what that might look like. i.“This is the emergency medicine exam. It’s highly likely that the prop I have been given shows a significant emergency. a.It might be a normal prop, but this is far less likely ii.This is not a test routinely reviewed by Emergency Physicians. a.I won’t be expected to have detailed in depth knowledge of subtleties b.In other words, the findings should be pretty obvious. iii.CTGs are done for ? foetal distress. It is therefore highly likely that this is what is shown on the CTG. iv.Therefore, even knowing nothing about CTGs, with the context of a woman in advanced pregnancy in abdominal pain, I would guess and say that the CTG is most likely to show significant signs of foetal distress. v.I know that CTGs measure foetal Heart Rate. vi.Therefore I will answer with the elements of the CTG shows foetal bradycardia and urgent obstetric intervention is needed to deliver the baby. a.I might not get all the marks, but hopefully I’ll get enough to pass. b.If I’m wrong, there are no negative marks, so what do I have to lose.” You might think that’s pretty out there. It is. And it’s certainly not a way to practice medicine in real life. But, in preparing for the examination, we are believers in using every strategy available when the occasion calls for it. If knowledge and experience fail, try stepping back and thinking about *why* you are being asked the question, rather than just the content of the question itself. Why is this a difficult question? Because of the limited numbers of attempts allowed. That is a greater stressor, than failing, because your brain goes into a future that doesn't exist yet and creates an outcome that may not occur, but could and with that causes doubt and fear.

Here are my thoughts:

|

AuthorShareThe Written Fellowship Course has its beginnings back in 2007, When Dr Kas started it at RPA in Sydney. It was then called the Kamikaze Course. Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed